The Rockwell Museum in Corning, New York, will open a major exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art Saturday as part of its programming for America’s 250th anniversary, highlighting work by living Native artists and their written reflections.

The exhibition, titled “Native Now: Contemporary Indigenous Art at The Rockwell Museum,” marks the museum’s 50th anniversary and coincides with the nation’s semiquincentennial. It runs through May 4 and brings together about 50 artworks by more than 30 Indigenous artists from across the United States.

Rather than framing the exhibition as a retrospective or historical survey, the museum and its co-curators told Urgent Matter the focus is on what it means to make Native art in 2026, not 1776.

“We are sort of big-tent America,” said Amanda Lett, the Rockwell’s curator of exhibitions and collections. “So we tend to see all of this as a part of American history, the American story.”

It opens as Washington ramps up plans for America’s 250th anniversary, a milestone the administration of President Donald Trump has turned into a political priority. The White House created a task force to steer the celebrations, centralizing planning across federal agencies and involving national cultural institutions.

“We had been planning this exhibition not especially with America’s 250 in mind,” Lett said. “We really just felt like this was just a great opportunity and excellent timing.”

The Rockwell Museum is a Smithsonian affiliate, a designation that connects it to the national museum network through education programs and resource sharing, but does not give the Smithsonian Institution authority over exhibitions or curatorial decisions.

“Content-wise, exhibition-wise, programmatically, they might as well not know we're here,” she said. “So, we don't really have the things that happen there happen here.”

Sign up for Urgent Matter

Breaking news, investigations and feature articles touching the art world written by Urgent Matter journalists.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Lett was asked again if the Rockwell Museum needed to be cautious about its Smithsonian affiliation in case the Trump administration did not approve of its “Native Now” exhibit or other initiatives.

“Maybe it's naive. We're not necessarily concerned,” she said. “The amount of money that we get from the federal government is minimal. We're very much continuing the course of who we are, and the kind of shows we want to put on, and the kind of dialogues we want to have.”

The exhibition is co-curated with Randee Spruce, a citizen of the Seneca Nation and member of the Heron Clan. Spruce said the exhibition was “bound to happen anyway,” whether it was America’s semiquincentennial or not.

“I get everybody wants to make a big deal out of the 250th anniversary,” Spruce said. She framed the moment through a Haudenosaunee lens, describing confederacy as a long-standing system built around collective responsibility and care — an idea she said extends beyond Native nations.

“We all have this collective responsibility to care for the Earth, and care for each other,” she said. “Bringing that into modern-day times, we should all be thinking like that as America is a big melting pot.”

Spruce said her involvement grew out of conversations between the Rockwell and the Seneca Nation’s Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural Center about how Native art was presented in the museum.

“They invited us in to take a look at their Haudenosaunee galleries and what’s been wrong, and to move those conversations forward,” Spruce said. “That’s where we started talking about how we should really hone in on getting a Native perspective on all the Native art that they have in their collections.”

From the start, both curators said the goal was not to speak about Native artists, but to let them speak for themselves. As a result, the exhibition’s wall labels were written entirely from artist interviews and correspondence.

“I’m not on the labels at all,” Lett said. “All of the labels are written by the artists themselves.”

The decision, she said, was deliberate, particularly in a museum that serves many students.

“It’s really important for, especially young people, to see living artists that are thriving and that are really on the cutting edge,” Lett said. “Yes, the past is compelling, and we need to look at it, but this current moment is also really exciting.”

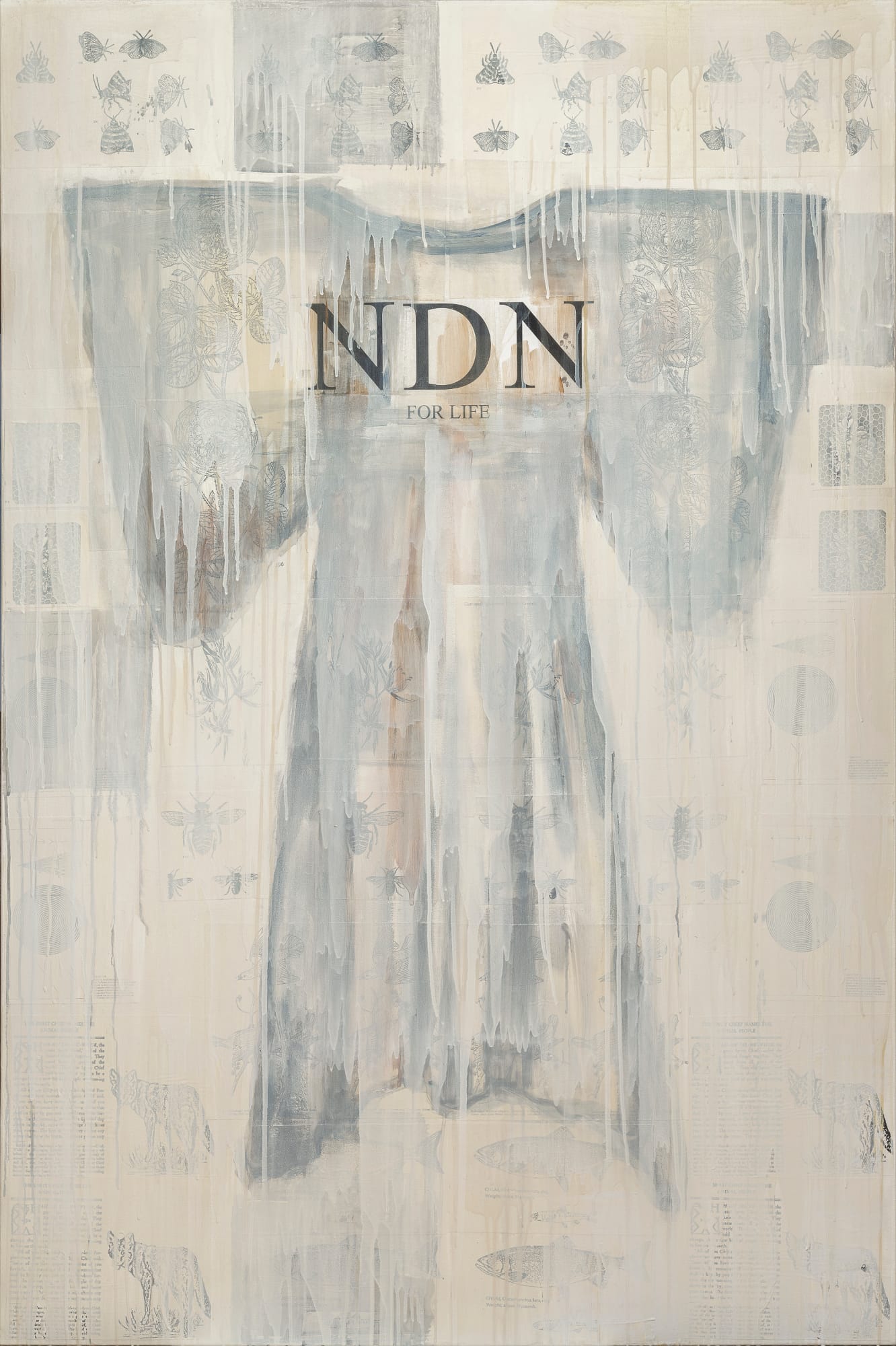

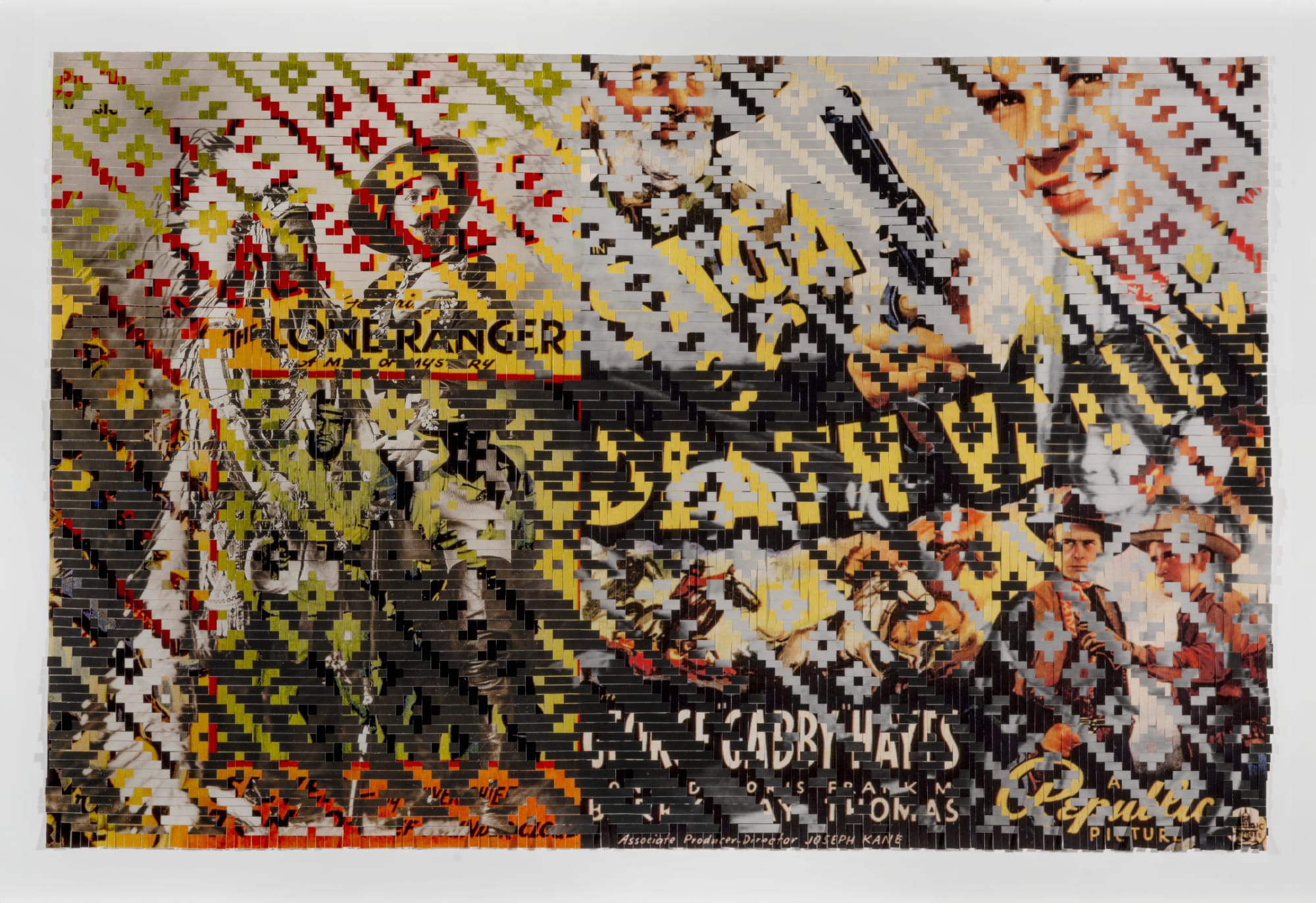

The exhibition draws primarily from the Rockwell’s own collection, built over more than two decades, along with several major loans through a partnership with the Art Bridges Foundation. Those loans include works by Jeffrey Gibson, Raven Halfmoon and Cannupa Hanska Luger.

Early press materials described the exhibition as organized into three sections: “Indigenous Landscapes,” “Past/Future” and “Thrivance,” a term associated with Native scholarship. That structure changed during the curatorial process.

“We actually ended up taking out ‘thrivance’ and replacing it with something else,” Spruce said. The change, she said, reflected an effort to move away from academic framing.

“When I was brought onto the project, there were already a lot of ideas,” Spruce said. “But I guess it’s my job to make it a little less academic and more meaningful.”

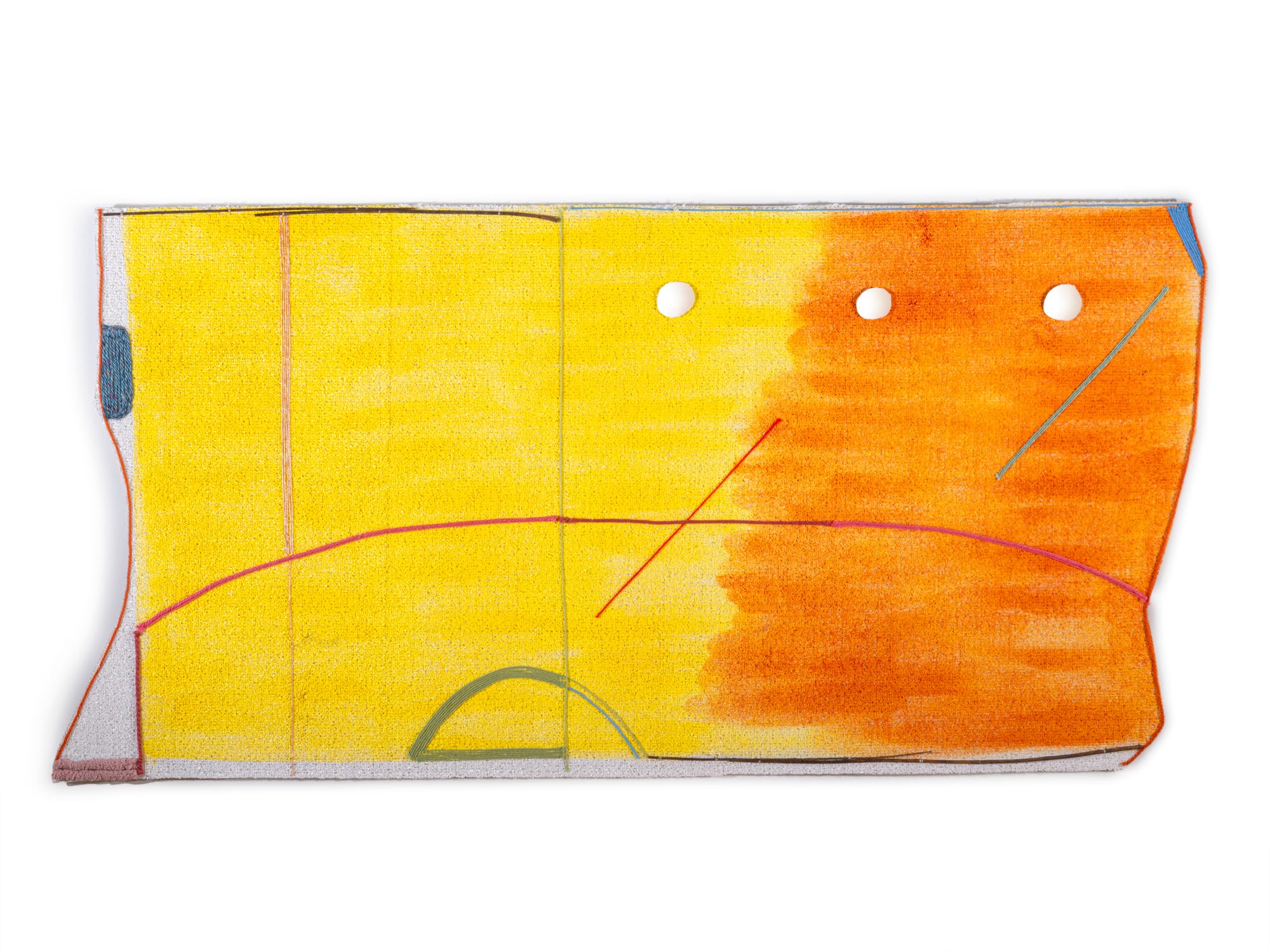

The final section is now framed around the idea of “always becoming,” which Lett said better reflects contemporary Indigenous art.

“This idea that we’re always changing, we’re always growing, we’re always moving,” Lett said.

Themes of land, survival, resistance and futurism remain central.

“Land ownership is really a foreign concept to Native peoples,” Spruce said. “We believe in a collective stewardship of the land, and a responsibility to care for not only the land, but everything that lives on it, and each other.”

Several works in the exhibition address those ideas directly. Spruce highlighted Teresa Baker’s Yellow Prairie Grass, which layers artificial turf with buckskin, yarn and acrylic.

“I believe that piece is about this kind of artificialness of land,” Spruce said. “But also having the natural materials on that as well is just kind of saying, this is a new material, obviously, but still making it our own.”

The exhibition also leans into Native futurism, particularly in works by Virgil Ortiz.

“He carries that knowledge of pottery in his work,” Lett said, “but he’s making aliens and spacemen and stuff like that out of traditional clay and slips.”

The artists in the show represent dozens of tribal nations across the country. “It really is sort of a coast-to-coast swath,” Lett said. “Washington, California, the Midwest, Louisiana, Georgia.”

Spruce said that range counters the assumption that Native cultures are monolithic.

“Different nations have different stories,” she said. “We all have different ways of expressing.”

The exhibition also includes work by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, who died in 2025. While the curators did not set out to memorialize her, they acknowledged her influence. “She’s such a force,” Lett said.

The curatorial process moved quickly, with planning beginning over the summer and installation unfolding over several days.

“We’ve spent the last two days just in the space moving art around,” Lett said. “It’s been fun.”

For Spruce, the collaboration represents something larger.

“I think it’s awesome that the Rockwell Museum wanted to have an actual Native representative to help out with this show,” she said. “I can only hope that other museums see that and follow suit.”