A new show at New York City’s Poster House museum features dozens of advertising and propaganda designs from fascist Italy, offering a stark warning about the resurgence of their symbols.

The show, “The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy,” was curated by Italian-born artist and author B.A. Van Sise, who spoke in an emailed interview with Urgent Matter about how fascist Italy’s artists “buckled” to the regime of Benito Mussolini.

“The mention of something is not the glorification of it, and I like to think we do a good job of talking about what’s happening behind all of this,” Van Sise said.

Among the works on view are propaganda and advertising posters created under Mussolini’s dictatorship, including a “magnificent poster” for the Blackshirts—paramilitary forces that enforced loyalty to the regime, Van Sise said.

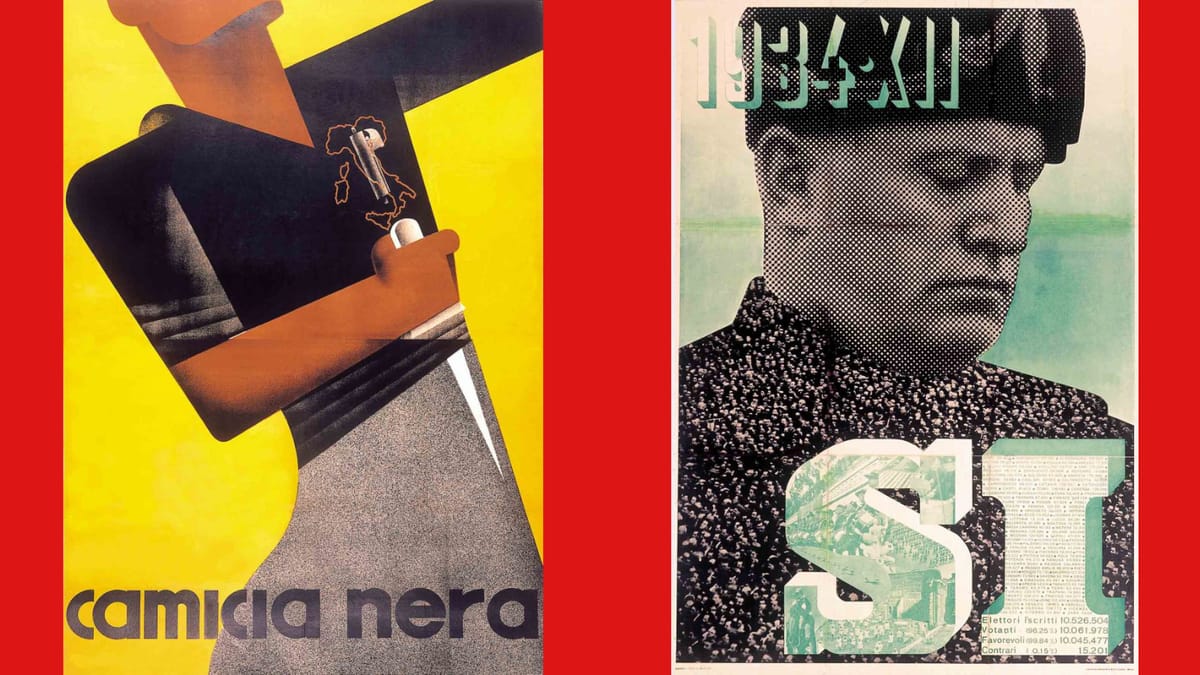

The 1933 poster Camicia Nera (Black Shirt) by Paolo Federico Garretto confronts the viewer with stark geometry: a diagonally angled torso clad in an inky black shirt, gripping a dagger angled toward the hip. The sharp silhouette contrasts against a bold mustard-yellow field.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Blackshirts routinely tortured and murdered political opponents, particularly socialists, trade unionists and journalists. One hallmark of their violence was forcing victims to drink castor oil, a laxative, as a form of humiliation and physical punishment. In many cases, it led to extreme dehydration or death.

Xanti Schawinsky’s 1934 poster Si shows Mussolini’s face dominating a field of typographic affirmation. And another “charming poster” promotes a motorcycle race in Portogruaro, where the regime sought to better the life of its citizens with a vaccine drive but instead killed children in the town with tainted doses.

“We talk about absolute successes in food independence and social welfare programs, but also colonization and the alliance with Germany,” Van Sise said.

“We talk about how Mussolini’s great love was a Venetian Jew, and also how he buckled to Germany’s racial laws and soiled the thousands-years-long relative success of Italian Jewry. We talk about both his popularity—which was immense—and his rigged elections, which were shameless.”

The show originated with Poster House’s executive director Angelina Lippert, who met with the Fondazione Massimo e Sonia Cirulli in Bologna, Italy, about the possibility of the exhibition three years ago, Van Sise said. The majority of the 75 pieces in the show come from the Cirulli Foundation.

Van Sise said the ephemeral nature of posters gives them power — they were never meant to survive — adding, “Nobody expects them to be saved.”

Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and her right-wing Brothers of Italy party, which grew from neo-fascist movements that emerged from the remnants of the Mussolini regime, has often rejected the label of “fascist” while invoking nationalist and traditionalist rhetoric that echoes elements of the Mussolini era.

Van Sise was asked to respond to how he sees the visual and cultural legacies of Italian fascism propaganda like the work seen at Poster House persisting or being rebranded in contemporary Italian politics.

“Everybody rejects the label of fascist for themselves. Nobody calls themselves a fascist because nobody needs to: a wink and a nod are enough for the true believers, and the idea is repellant to the wary,” Van Sise said.

“So, it manifests as certain leaders toeing very, very fine lines to let the crazies know they're fellow travelers and let their detractors convince themselves it's more benign than they imagine.”

Van Sise said the world is seeing a global rise in traditionalist rhetoric, which he described as “primarily driven by uncertainty.”

“This is what always happens in these sort of retro, fascist movements—people are nervous, uncertain in their uneasy epoch, but remember through pink lenses a supposedly simpler, clearer time when everybody was happy and healthy and looked like you and thought like you,” he said.

“That time never existed, of course. In Homer’s Odyssey they talk about a drug, nepenthe, that doesn’t actually fix your problem but instead quells your sorrows with forgetfulness. A lot of these movements are feeding nepenthe to their followers: whatever problems you might have, we can return to this mythical time—just so long as you forget, forget, forget.”

The curator said that, when writing the exhibition, he thought about how Italian fascists of the Mussolini era “pined to be ancient Rome again” while “a lot of fascist movements are stepping back into familiar symbolism.”

“Though today, it’s not the nation’s best artists—certainly the case for the fascists of Germany and Italy, who had their respective nation’s most talented at their disposal—but dorks on computers generating AI slop propaganda,” he said.

But the resurgence of aesthetics from prior eras is not unique to any singular current movements, Van Sise said, nor has symbolism ever been unique to a specific group.

“In the American Civil War, both the Union and the Confederacy had George Washington on their money. In World War II, the United States, with their eagle, was fighting the Germans with their eagle and the Italians with still their own,” he said.

But what Van Sise said he finds interesting is how current ultranationalist movements lean into imagery and styles that historically would have been seen as "enemy."

“For instance, Western political movements making social media posts where the ChatGPT prompt they’re using has to, has to, has to, has to include the phrase ‘German propaganda poster’ or ‘Soviet propaganda poster,’” he said. “It’s impossible that it doesn’t.”

Still, Van Sise said he sees the show as more of a design exhibition than a study of political ideology, though the two are “turns of the same coin.” He said the exhibition explores how Italy’s artist class “buckled—obeyed in advance, really—to the larger regime and became its tool.”

Many artists working in stile liberty, or Italian art nouveau, abruptly shifted their styles when it became politically convenient. As an artist himself, Van Sise said that wholesale change was “shocking and remarkable.”

“That’s also a story of political ideology: fascism was scary. And for some, it was awful sexy,” he said. “And what’s so scary and sexy that it makes an entire society throw aside its own values?”

He described the exhibition as “wordy—it’s got more text than Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” saying that the show caters to visitors interested in design while those drawn to history will find “triumph, colonization, war.” He added, “in the end, our exhibition—like the Italian people—hangs the villain.”

Van Sise was asked how museums like Poster House can present fascist imagery responsibly without inadvertently amplifying it but instead turned the question on its head.

“How can museums refuse to present fascist imagery? Museums have an obligation to inform people, ideally wholly and accurately,” he said. “As far as I know—and I’ve checked—right now Poster House is the only museum in the United States talking about fascism.”