The U.S. Justice Department has released photographs from Jeffrey Epstein’s properties that show the interiors of his homes in unusual detail, including dozens of artworks and decorative objects that were later sold off quietly at auction for relatively low prices.

The photographs were released through a court-approved disclosure mandated by Congress and were not intended to catalog Epstein’s art holdings. However, comparing them with auction records and online marketplace listings shows that many works visible in his homes later sold as reproductions or decorative objects, often without documented provenance.

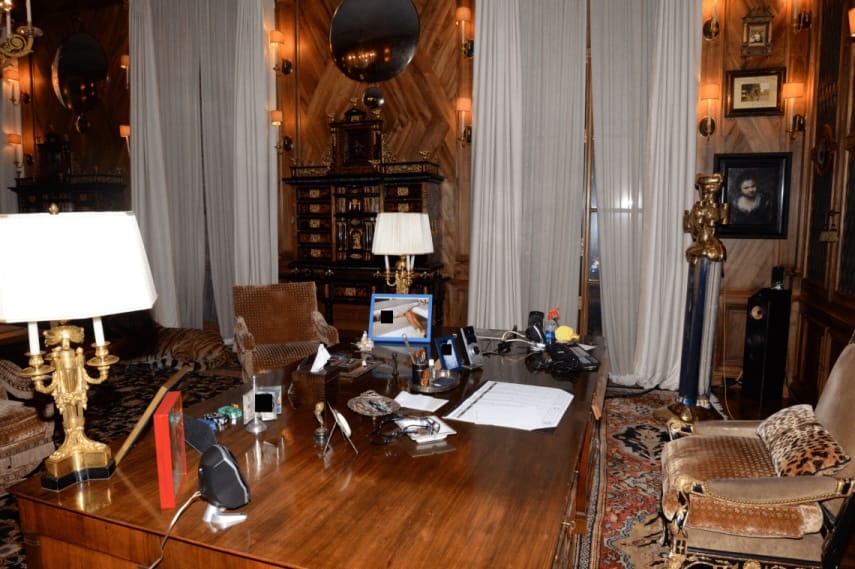

Beyond identifying objects that later surfaced at auction, the photographs show how those works were staged inside Epstein’s homes. In one room, a life-size bronze nude sculpture appears suspended from the ceiling and dressed in a bridal veil. This detail is absent from the auction listing, where the same work later sold as a conventional editioned sculpture.

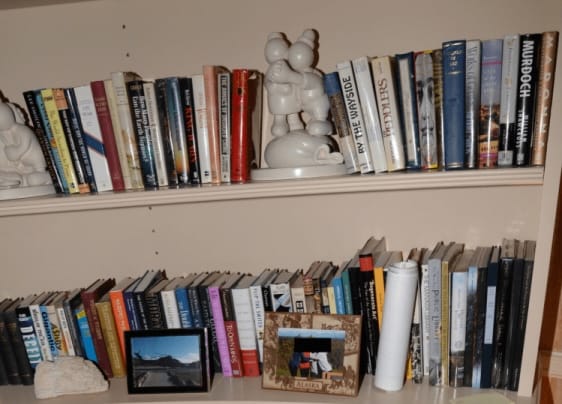

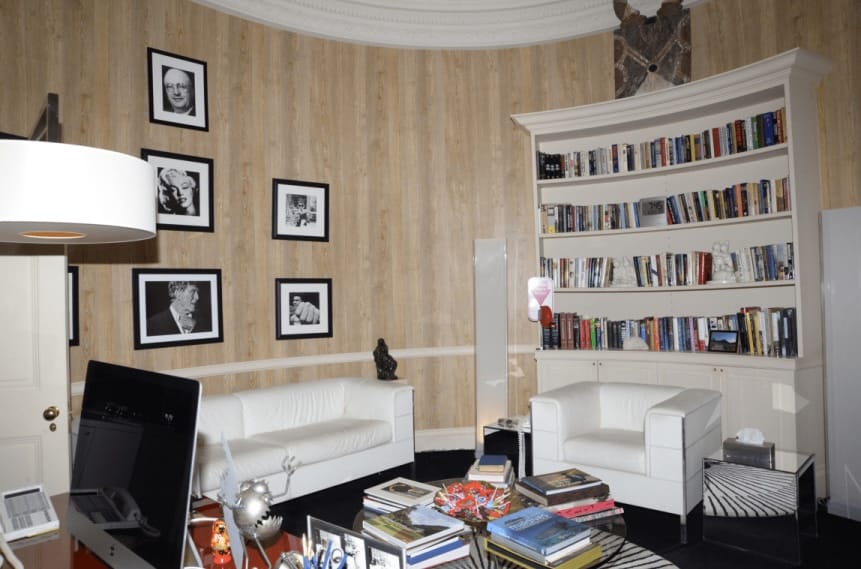

Elsewhere, museum-grade frames were used to elevate inexpensive reproductions, while well-known art images were placed in back rooms, hallways and utility spaces.

The photographs also show reproductions of famous artworks reduced to decoration, treated as visual filler rather than as objects of value. An apparent mass-produced reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa appears mounted high in a utility space at Epstein’s Little Saint James property, above doors surrounded by ladders, storage bins and mechanical equipment.

Another image shows a framed reproduction resembling a cropped detail from Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe mounted along a bathroom corridor beside a towel rack.

The photographs showing Epstein’s art were embedded within roughly 3,000 images from a much larger Justice Department release, most taken inside his Upper East Side mansion. The images were not organized or grouped by room, and analyzing their contents required extensive data sorting and forensic review by Urgent Matter.

As related images were grouped, a more complete picture emerged of how art and décor functioned within the home. One cluster shows what might be described as a “tiger room,” anchored by a taxidermied tiger amid medievalizing décor that evokes a stripped-down, almost theme-park version of a museum gallery. It is closer to a cheap imitation of the Met Cloisters than a private collection.

Another grouping centers on the headline-making painting depicting Bill Clinton in a blue dress, which first came to light in August 2019, just days after Epstein’s death in a Manhattan jail cell. But analyzing the Justice Department photos reveals how it was positioned within Epstein’s home, rather than as a lone shock piece.

Urgent Matter compared the Justice Department photos with public auction listings, museum reproduction catalogs, and online marketplaces like Etsy and eBay. This comparison showed repeated types of objects, display methods, and staging choices that influenced how the rooms looked to visitors.

Previous reports from the New York Post and Artnet News provide more details about what happened to Epstein’s art after his death. The contents of his Upper East Side townhouse were sold in bulk by a New Jersey auction house, Millea Bros., instead of through a curated sale.

Ahead of the Justice Department release, the New York Post broke that Millea Bros. had been selling art and décor linked to Epstein’s Upper East Side home through a series of quiet “select” sales. The Post said these sales had brought in at least $100,000, and the listings did not name Epstein as the source, even when the items looked like those in well-known interior photos.

An attorney for Epstein’s estate told the Post that the townhouse contents were sold in bulk as part of managing the estate and compensating victims.

Artnet, after reviewing the Post’s reporting and auction listings, reported that this was not the first time items linked to Epstein’s properties had been sold publicly. It mentioned an earlier sale at Neely Auction of a painting by Brooklyn artist Limor Gasko, which was said to be commissioned for Epstein’s Palm Beach property and sold for $8,500.

Artnet also identified a giclée on canvas listed as “After Kees van Dongen,” which sold at Millea Bros. for $275. This work does not appear in the Justice Department photos.

But the Millea Bros. listing corresponded to a giclée reproduction of Femme Fatale, a well-known composition by van Dongen that sold at a 2004 auction by Christie’s for $5.9 million.

Photos reviewed by Urgent Matter show the reproduction closely mirrored the original painting’s composition, while the auction house listing lacked any indication of authorship beyond the catalog designation “After Kees van Dongen.”

According to Artnet, the giclée was framed by Eli Wilner & Company, a firm known for its frames used in museum collections and at the White House. If that painting did come from Epstein’s estate, it is telling that the cheap reproduction, which sold for only $275 at auction, was presented in his home in such elegant packaging.

Auction records reviewed by Urgent Matter include dozens of additional works that either resemble objects visible in the Justice Department photographs or reflect the same categories of decorative and editioned art seen in the interiors.

In some cases, auction listings closely resemble objects visible in the Justice Department photographs. In others, the records diverge. Certain works appear only in the photographs and not in the auction catalogs, while other works sold at auction do not appear in the released images.

For instance, Epstein’s massage room featured large nude artworks — seemingly oil paintings mixed with photographic works — that Urgent Matter was unable to identify in the auction listings. At the same time, Millea Bros. sold dozens of nude or sexually charged works that do not appear in the Justice Department photographs.

While some of those lots may have originated from Epstein’s estate, others may have come from different consigners, highlighting the incomplete and overlapping nature of the visual and auction records.

But the Justice Department photos reveal that Epstein anchored each room in his mansion with such statement pieces, not always nudes, though the strategy shifted between reproductions of known works and legitimate, but low-valued, artworks by mid-tier or emerging artists.

In one room that could be described as the “piano room” for its Steinway & Sons baby grand piano, Epstein anchored the aesthetics around an actual collage by French artist Jean-Charles Blais titled Personnage, which was seemingly bought by Epstein from Artcurial in Paris in 2005. The artwork did not get a single bid in the Millea Bros. auction.

Meanwhile, another room, with cheetah-print barrel chairs, was anchored by a reproduction of Head of an Old Man with a Full Beard and Bald Head (Study for a Neptune) by the Flemish old master Jacob Jordaens. It sold at auction for $250.

Works offered at auction from across Epstein’s mansion included a North European Baroque terracotta bust, a modern papier-mâché sculpture, oil paintings described as “in the manner of” William Blake and Giuseppe Nogari, large contemporary paintings by Eileen Roaman Catalano, Jorge Alvarez, and Enrique Miralles Darmanin, and a silver gelatin photograph of Albert Einstein by photographer Philippe Halsman.

Sign up for Urgent Matter

This holiday season, consider a paid subscription to Urgent Matter to support independent journalism and to have our weekly recap newsletter, breaking news updates and subscriber-only articles delivered to your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The listings generally did not include documentation establishing ownership history or confirming placement within Epstein’s properties. Many relied on stylistic descriptions rather than firm attribution. Some entries included brief provenance notes, but none identified Epstein as a prior owner.

Among the most revealing moments of Epstein’s curation comes from a Justice Department photograph of a sculpture of a nude woman, shown hanging from a rope over the home’s main stairway. In the photos, the figure is shown wearing a bridal veil, a costume that changes the sculpture from a neutral figure into a staged scene. The bridal veil does not appear to be a part of the original artwork.

Millea Bros. sold that bronze sculpture, attributed to French artist Arnaud Kasper and titled Female Nude, for $1,500. The listing says the work is signed, cast at La Fonderie Chapon, and is number six out of an edition of eight.

Urgent Matter also found an editioned Tom Otterness maquette called Free Money in the Justice Department photos, where it was used as a bookend. Millea Bros. sold this sculpture for $5,000.

That maquette was featured in an apparent office space that also featured famous photographs of celebrities, including Muhammad Ali, Marilyn Monroe and Robert Redford.

In the Justice Department photographs, that room seemed anchored by a sculptural head with an elongated neck and simplified facial features that echo Amadeo Modigliani. While that work was untitled and unsigned, it sold for $2,250 at auction.

Japanese folding screens showing Mount Fuji and fishermen are featured in the photos, and appear to have been in the entryway to Epstein’s home, making them the first artworks guests would see.

An apparently identical pair previously sold at Christie’s for $9,200 and Urgent Matter found Etsy and eBay listings with nearly identical designs, priced from $150 to $600, often labeled as “Japanese style” or “Asian folding screen.”

A tall gilt-bronze and marble pedestal clock is seen in the photos, looking like clocks credited to Jean Adolphe Lavergne. Millea Bros. also sold a sculptural bronze mantel clock attributed to Lesieur à Paris as part of the estate sale.

And the photos show how such art appeared in every corner of Epstein’s home. One photograph shows a large decorative ceramic plate bearing a crowned coat of arms motif, hanging in the kitchen. The plate was later sold as a 19th- or 20th-century French polychrome plate with a Rouen underglaze mark and wire for wall hanging.

The Justice Department images also show stacks of interior design materials, including what appears to be a catalog from Artefacto, a Brazilian manufacturer known for high-end, mass-produced furnishings. Its presence frames the furniture as items to be ordered, not commissioned, pointing to a buying process closer to procurement than collecting.

Another photo shows a typed ledger with dozens of payments made over several weeks in late 2011 and early 2012. The entries include political donations, household services and art-related expenses. For example, there is an $834.80 payment to Robert J. Hennessey Photo for “art photos” and a $3,400 payment to Peter Perez for “art conservation.” The ledger does not name any specific artworks.

Selling everything in bulk highlights the limits of the authority these objects once had. Once removed from their original setting, a $275 print remained just a $275 print, and a sculptural nude became a $1,500 auction item.

A companion article examines the limits of the Justice Department photo release and the challenges of tracing artworks through the estate dispersal.