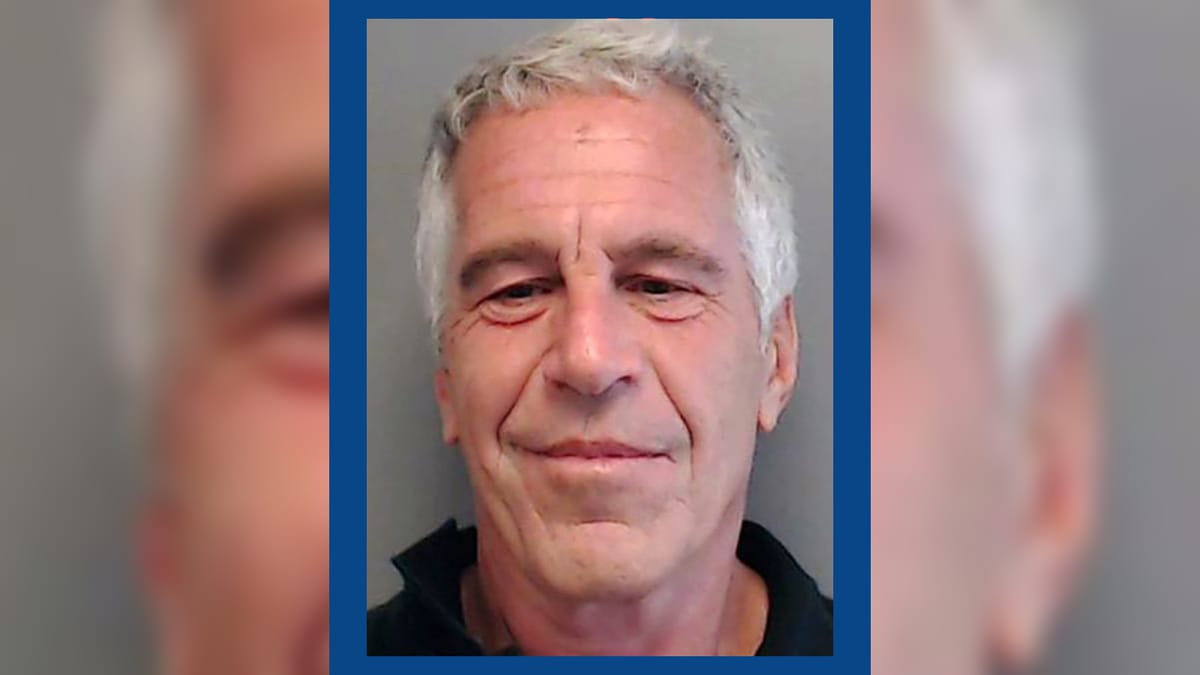

Jeffrey Epstein’s internal emails reveal private high-value art deals involving financier Leon Black, including carefully shielded exchanges of works by Paul Cézanne and Alexander Calder, and complex tax planning tied to a Picasso purchase from mega-gallery Gagosian.

The Epstein files, released this week by the House Oversight Committee as part of a 20,000-page production, offer an unusually detailed look at how art moved through the financial systems surrounding Black. Urgent Matter reviewed more than 150 pages of emails between Epstein and Black’s advisers between 2012 through 2019, with the heaviest correspondence between 2014 and 2016.

Black’s relationship with Epstein has long been the subject of extensive scrutiny. In July 2023, documents revealed that Black had reached a $62.5 million settlement in January 2023 with the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Epstein owned the private island Little St. James.

Prosecutors were weighing a lawsuit that would have claimed Black channeled enormous amounts of money to Southern Trust, Epstein’s firm, to support his sex trafficking enterprise. Under the deal, Black was released from liability.

Black has also been under scrutiny after Black’s firm Apollo Global Management commissioned an independent investigation that found he had paid $158 million to Epstein for tax and estate planning services between 2012 and 2017, corresponding to the dates of the emails.

The U.S. Senate Finance Committee later suggested the total could be closer to $170 million and questioned whether some of Epstein’s strategies helped Black avoid substantial gift and estate taxes. The newly released emails deepen those concerns.

Picasso agreement with Gagosian emerges as a core transaction

Although the documents mention Cézannes and Calders, a far more intricate negotiation appears around the purchase of a work by Pablo Picasso from Gagosian by Black. The emails do not specify which Picasso was being purchased. It is unclear from the emails reviewed whether the Black/Gagosian Picasso transaction was ultimately completed.

In a November 20, 2015 message to Melanie Spinella, who appeared to work for Black based on context, Epstein expressed disbelief at the absence of formal paperwork.

“Gagosian. No written contract??!! Fishy to me,” Epstein wrote. “Who transfers 100 million dollars overseas without a contract?”

Epstein also noted that Gagosian was “on the tax dept radar.” In 2016, Gagosian agreed to pay $4.2 million in back taxes to New York State after an investigation into unpaid sales taxes. Epstein urged caution: “Don’t want you pulled into a scandal.”

As negotiations on how to structure the Picasso purchase continued, Epstein insisted in an email to Brad Wechsler that Black needed to personally approve any plans on whether to assign the agreement to Black, his wife Debra, their children or family trusts, and what would happen if those trusts lacked the assets to complete the final payment.

The most detailed explanation appears in a message from Heather Gray, an attorney involved in structuring Black’s art transactions. In it, she lays out dealer Gagosian’s concern that Black could assign the agreement to a trust with no money, leaving the gallery unable to collect.

“As you know, we have structured this agreement with the Buyer as either Narrows Holdings LLC or AP Narrows LP, and given both of those entities the right to assign the agreement to any one among Leon, Debra, the kids, or family trusts including APO1 and APO2,” Gray wrote in an email to Epstein.

Gray wrote that Gagosian wanted Black’s camp to agree that, if either entity assigns the agreement to someone else, Black’s companies would not be discharged from its liabilities under the agreement.

“Larry is concerned that we might assign to the Black kids or to a trust that has no assets, and then when he has to sue us because we don’t make the final payment of the purchase price but have possession of the art, the entity/person to which we have assigned the agreement has no money,” Gray said. “I think this is a valid concern and that we should agree to it.”

Unlike the Cézanne and Calder discussions, which focus on confidentiality and exchange mechanics, the Picasso correspondence is dense with legal, inheritance and payment-risk issues.

In a later thread, Epstein took credit for modifying the Gagosian contract to organize the structure of the purchase of the Picasso as a gift trust in case Black were to get divorced, as well as “protection that resulted in your having no liability.”

Cezanne and Calder 1031s

Some of the most revealing exchanges appear in emails between Epstein and Heather Gray, an attorney involved in structuring Black’s art transactions.

In 2015, Gray detailed how Epstein and Black previously arranged a 1031 exchange involving a Calder work and how they were preparing similar structures for Black’s planned acquisitions of Cézanne paintings.

Back in 2015, collectors could still swap one artwork for another under a tax rule known as a 1031 exchange. A collector could sell a piece, roll the money straight into buying another artwork and delay paying taxes on the sale. The rule became a popular way for wealthy buyers to move into more valuable works without taking a tax hit right away. Congress changed the rules so 1031 exchanges can only be used for real estate, not art.

“As you will recall, we used this same exchange agent last year on the Calder 1031,” she wrote in 2015. “Leon did not want to use a gallery because he was concerned about confidentiality.”

Gray explained that a commercial intermediary had proven useful during potential IRS review, but offered limited assurance on state sales-tax issues. Even so, she stressed that confidentiality drove Black’s decision-making.

“He said to use the same exchange agent as before,” she wrote, “because he was extremely concerned about confidentiality with the purchase of the Cezannes.”

Bronzes linked to Black’s collection appear as recurring topics in the emails, especially in the context of valuation challenges. On December 1, 2015, Epstein wrote to Wechsler that they needed to resolve concerns raised by Ada, whose last name was unknown, about how certain bronzes were being assessed.

“We should put to bed once and for all Ada’s concerns regarding the bronzes,” he wrote. He added that Alan, whose last name was not provided, should give “valuation ranges rather than estimates,” indicating that precise appraisal numbers were required before other planning steps could progress.

While the bronzes were not part of the Picasso dealings, the valuation questions affected other planning steps because Epstein and Black’s team were modeling multiple artworks simultaneously.

Epstein's deep involvement in Black's art affairs

Another revealing email sent by Epstein was a “detailed constructive list,” effectively a running agenda of overdue items which included a reference to an unnamed “art partnership,” which he said needed immediate attention.

“Art in art partnership.??! .overdue ?!” he wrote.

The list situates the art partnership in a broader network of cultural and commercial holdings. He referenced digital marketplace Artspace “folding” and Regan Arts, a publishing imprint, two companies within Black’s cultural holdings. Rather than treating them as creative enterprises, Epstein models them as assets with gains or losses.

In an October 26, 2015 message, Epstein wrote that Phaidon and Artspace together had cost about $96 million, later adjusted to $106 million. He projected a resale value between $8 million and $15 million — meaning a large loss on paper. He then estimated how much tax relief such a loss could produce.

While Black has always been known as a major collector, the newly released records show internal warnings from Epstein about Gagosian and the complex agreement that went into buying a Picasso from the previously tax-embattled mega-gallery, as well as the breadth of Epstein’s involvement in reorganizing cultural businesses like Phaidon and Artspace and Black’s estate and inheritance structure, especially involving art.

All of this provides new context to congressional questions about whether Epstein’s guidance helped Black minimize taxes through art-related transactions.

It also underscores how fraught the relationship had become in Epstein’s final years. In one message, he sought to renegotiate his compensation and warned that he would no longer continue working without payment.

“If I can find the time to work on your project, which is not by any means certain as I have said, I hope you understand that it now will have to be under my standard terms and conditions, and well documented so as to avoid any more of the he-said she-said,” Epstein wrote to Black’s camp.

“I never want to have any more uncomfortable money moments with you; I find it very distasteful. So, to be clear, my terms are as follows. I will only work for the usual $40 million per year. It needs to be paid $25 million upon signing an agreement, $5 million every two months thereafter for six months.”

Earlier, Urgent Matter broke the news that explored direct purchases from emerging artists.

Stories like this take time, documents, and a commitment to public transparency. If you want more reporting that uncovers how power operates behind the scenes of the art world, subscribe to Urgent Matter and support our work directly.

Sign up for Urgent Matter

Breaking news, investigations and feature articles touching the art world written by Urgent Matter journalists.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.