A series of advertising posters made by artist Dorothy Waugh to increase tourism to U.S. national parks during a significant Great Depression-era expansion has gone on view together for the first time in a museum exhibition.

New York City’s Poster House museum is showing all 17 posters Waugh made for the campaign in an exhibition titled “Blazing A Trail: Dorothy Waugh’s National Parks Posters” through February 22, 2026. The exhibit is accompanied by a book by the same title, written by curator Mark Resnick and published by Rochester Institute of Technology Press.

The exhibition arrives as the National Park Service faces renewed political attention under President Donald Trump’s second administration, which has proposed deep cuts to park staffing and reopened large areas of federal land in Alaska to energy development.

Several executive actions this year have rolled back conservation rules affecting preserves managed by the NPS and adjacent public lands, prompting concerns from lawmakers and advocacy groups about the system’s long-term stability.

Against that backdrop, Waugh’s posters, created to rally public support for an expanding park network under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, take on fresh relevance as the future scope and funding of America’s parks again become subjects of national debate.

“Although the exhibition isn’t political or polemical, I do want the viewer to be informed of the role our government has vigorously played, over many administrations, in stewarding the national parks—which have famously been called ‘America’s best idea’ and are emulated around the world,” Resnick told Urgent Matter.

“That’s not to be taken for granted; and for many viewers, it will raise the question of whether, amidst today’s heavy cuts to the NPS’s staff and budget, the parks will flourish as they have ever since President Roosevelt’s tenure.”

Waugh’s posters pair crisp silhouettes with bold, limited color palettes to cast the parks as sites of wonder. In works such as Life at Its Best and Mystery Veils the Desert, she depicts adventure with hikers and riders on horseback.

In another, she casts a trumpeter swan against fields of blue and red, invoking the colors of the American flag with the text “Save Our Wildlife” to impart national pride in the parks.

Resnick called Waugh’s posters “significant cultural records of the Great Depression” rooted in Roosevelt’s belief that “tourism in America’s magnificent parks would be crucial to restore the country’s shattered morale and economy.”

“He backed up that conviction with New Deal programs like the massive Civilian Conservation Corps, which helped to ready the parks for tourists,” Resnick said.

Resnick said the campaign’s posters bore new messages, focusing on the national parks system as a whole, versus specific parks, as a “shared treasure that could help unify the fractured country.” The posters also promoted national parks as places to visit for affordable, year-round recreation.

“I’d say the posters were tourist materials and propaganda, the latter in the most affirmative sense of the word,” Resnick said. He said her poster campaign increased visitation to America’s national parks by 250%.

Until then, the national parks were primarily promoted through advertising by railroads that had lines serving regions for individual parks. Those campaigns were primarily focused on boosting train travel, which had plummeted during the Great Depression.

“Not surprisingly, railroad posters were doubling down on depicting specific parks that the railroad served or specific trains and their amenities,” Resnick said. “These posters employed relatively little graphic design.”

Waugh’s successful poster campaign also marked the first time the federal government handed a major visual initiative to a single designer—let alone a woman—and the circumstances behind her commission “could not have been more unusual,” he said.

“How Waugh landed the assignment is a story of raw talent and persistence combined with family connections and being in exactly the right place at the right time—a somewhat miraculous combination,” Resnick said.

Waugh was initially hired by Conrad Wirth, a senior NPS official who would eventually lead the agency, as a landscape architect for a Civilian Conservation Corps project. It was under Wirth that she later took on the poster design campaign.

“Wirth had been her father’s star landscape architecture pupil and knew quite well her varied abilities,” Resnick said, calling Waugh a “polymath” and “Renaissance woman.”

Waugh’s father had founded the first landscape architecture program at a public university, at what is now the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

“After Waugh saved the day on that project, she had Wirth’s steadfast backing as she successfully advocated that the NPS launch its first-ever major promotional campaign,” Resnick said.

The only other time the government had launched such a major campaign was during World War I, when President Woodrow Wilson’s administration outsourced the design of realist propaganda posters to New York’s Society of Illustrators, a group made up entirely of men.

Sign up for Urgent Matter

Breaking news, investigations and feature articles touching the art world written by Urgent Matter journalists.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

By single-handedly designing an entire campaign of modernist posters, especially as a woman, Waugh “set the stage for what would become a torrent of government posters,” Resnick said.

The exhibition has a section devoted to those, too, including works from the Federal Art Project in the late 1930s and others produced by numerous agencies through the 1980s.

“No 1935 visitor could have failed to notice how new Waugh’s posters looked. But with such modernism now far more deeply implanted, it’s important to remind today’s viewers that Waugh was blazing trails,” Resnick said.

Urgent MatterAdam Schrader

Urgent MatterAdam Schrader

“That applies, too, to the major inroads she made in fields that, today, may be more open to women. I’d also like viewers to consider a subtext of the exhibition: how subject to chance it is for even a great talent to have the right opportunity. And even if they get that opportunity, and receive some acclaim during their lifetime, how easy it is to fall off the radar map as time passes.”

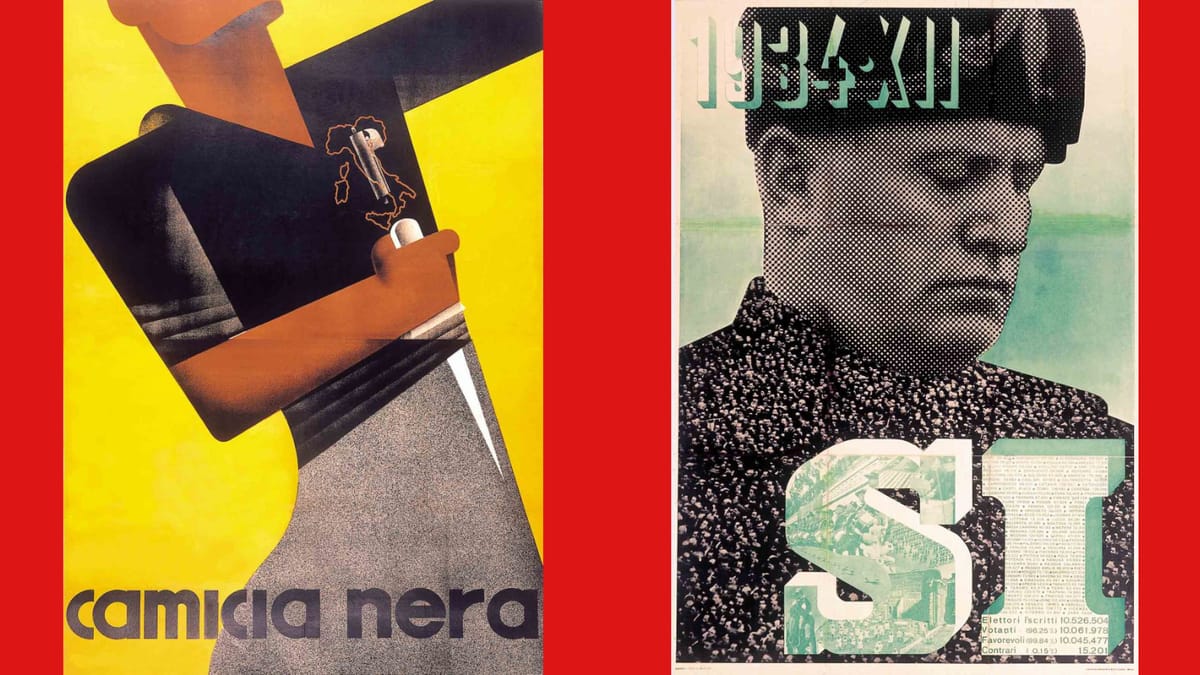

The show runs at Poster House simultaneously as “The Future Was Then: The Changing Face of Fascist Italy,” which features dozens of advertising and propaganda designs from fascist Italy, offering a stark warning about the resurgence of their symbols.

Correction 8:03 p.m. November 18, 2025: An earlier version of this article stated that Waugh began her government work as a landscape architect for a Civilian Conservation Corps project and was later hired by Conrad Wirth for the poster design project. Wirth hired Waugh for the CCC project, and it was under him that she later created the poster campaign.

Stories like this take time to schedule and conduct interviews, as well as additional research. If you value independent arts journalism, please subscribe to Urgent Matter and support our work directly.